Michelangelo was only 25 when he completed Pietà, a marble sculpture depicting Mary holding the lifeless body of her son, Jesus. His Pietà was so astonishingly beautiful that the Italian art community crowed that Michelangelo had surpassed “not only the sculptures of all of [his] contemporaries, but even those of the ancient Greeks and Romans themselves — the standard by which all art was judged.”†

By the time he was 29, Michelangelo had finished his second masterpiece, David, a sculpture that convinced the remaining skeptics of his mastery over marble and his unprecedented command of the human form.

There are no adequate words to describe the sort of giftedness that comes along maybe once every few centuries. Leonardo, Mozart, Einstein, Rembrandt, Beethoven, Michelangelo — the names are so few, we could probably list them all in a paragraph or two.

Though they lived and died long ago, their talents still astonish us today. They saw things so differently that history bent in their presence and was never quite the same again.

The great never seem to lack self-confidence. Aware of their own extraordinary abilities, they become driven by urgent ambition and a sense that they have been given an opportunity to make history.

Pope Julius II was also ambitious, but not great. But he was wealthy, so he purchased greatness. When he saw the Pietà, Julius declared that Michelangelo should be the one to design and sculpt his future tomb. It would be a tomb for a great Pope, which is how Julius saw himself, and in those days you didn’t disagree with the Pope if you wanted to keep your head. The tomb would measure 34 by 50 feet and include more than 40 life sized statues, the greatest of which would be a ten foot statue of Julius himself, all standing atop ornate marble columns and arches.

Michelangelo was enthusiastic about the project, which would give him an unprecedented showcase for his talents as a sculptor. But as luck would have it, the Warrior Pope, as Julius II was known, managed to deplete the papal treasury by pursuing a costly conflict with land barons to the south. The tomb project was put on hold. Not wanting to lose Michelangelo to other art patrons, Julius commanded Michelangeo to fresco the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, instead.

Only once before, as an art student, had Michelangelo worked in fresco, and then he was merely an assistant. Fresco is a technique in which pigments are applied to wet plaster on a wall or ceiling, creating a permanent “painting” in which the colors are locked into the plaster. For a variety of reasons, it is considered one of the most technically difficult art mediums to master.

Self-confident, ambitious, convinced of his own abilities and determined to leave his mark on history, Michelangelo agreed to fresco the ceiling, certain that he could learn what he needed to know as he went along.

I can be arrogant and self-confident to the point of folly, but I have a hard time imagining the sort of arrogant self-certainty that convinced Michelangelo that he could create a masterpiece on the Sistine Chapel ceiling. But among the truly great, such confidence is not an uncommon trait.

The Mercury astronauts had it. Richard Dawkins has it. Bill Clinton exudes it, but so do a great many men and women who run for our highest offices. Babe Ruth had it, as did Martina Navratilova and Katarina Witt. What they all seem to share is the inability to consider the possibility of failure. They are convinced of their greatness, their genius, their skill, and that fact leads them in everything they do.

Michelangelo took an enormous risk, but one balanced by rare talent. His ambitious risk-taking left us with one of the greatest works of art ever attempted.

If greatness demands risk-taking to show itself, is it possible that timidity prevents those of us who are merely average from making the most of our gifts and talents?

Jesus told a story in Matthew 25 to illustrate something about the Kingdom of God. A land owner gave his servants money to invest while he was away on a trip. To the most gifted, he gave five bags of gold. To another he gave three, and to the last he gave one. When he returned, he praised the first two servants, who risked everything and managed to double their investments. But the last servant was afraid to fail; he had buried his gold for safe-keeping. That servant was punished for his timidity. Jesus ends his story this way:

To those who use well what they are given, even more will be given, and they will have an abundance. But from those who do nothing, even what little they have will be taken away. — Matthew 25:29, NLT

This parable is not about money, but about the opportunities that life gives us to use our gifts and abilities well.

Michelangelo took a huge risk in attempting the Sistine Chapel, and frankly, it may not be his greatest work. It certainly isn’t perfect. He began with the story of Noah’s ark, and from the floor of the chapel the figures in that panel are too small and crowded. The scene lacks emotion. There are too many elements in the composition, too many stories being told.

This was the scene that took him the longest to complete. He even became discouraged by it, because it revealed how difficult fresco could be. He had trouble with the plaster, trouble with his colors, trouble getting his bearings on the huge ceiling.

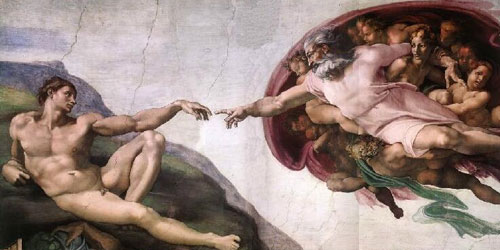

But he did learn. By the last scenes on his ceiling, where God is in the act of creation, Michelangelo’s figures are grand, beautiful, and full of dramatic looks and gestures. Those panels include what is probably the iconic image in all of religious art — God reaching out with his finger to create man in his image.

If Michelangelo had played it safe and buried his talents in sculpture, the world would have been forever deprived of that beautiful, reaching finger of God.

One of the interpretations of Matthew 25 is that God has not made us equal, but he has given every one of us a gift, a talent, a unique set of abilities and opportunities. We get to choose whether to use them boldly, or timidly.

Do we take a risk or play it safe? It’s surprising how often that question comes up in life. I have a very strong instinct for playing it safe, but I have a feeling Jesus wants to teach me boldness, courage, audacity, a willingness to fail in the pursuit of great things.

The Sistine Chapel ceiling wasn’t empty when Michelangelo started his work. It had been frescoed earlier by Piermatteo d’Amelia as dark blue heavenly scene with gold stars twinkling. Michelangelo’s first act was to chisel d’Amelia’s safe and boring scene onto the floor, after which there was no turning back. It was an monumental risk, but look what that risk has given us.

Photo credit: Wikipedia

† Michelangelo and the Pope’s Ceiling, Ross King, Penguin Books, 2003. This is a fascinating and extensively-researched book about the life and times of Michelangelo and his labors on the Sistine Chapel. I highly recommend it.

Thanks Charlie! Great article! Very inspiring!

Ah, even the great Michaelangelo had to learn. It’s been said that gifts come in seed form. The genius is there but must be developed.

I’ve bumped into too many genius’ in seed form, who were unwilling to put in the time and effort to bring their talents to full maturity. Writer friends are fond of saying, “Writing takes 10% inspiration and 90% perspiration.”

That’s something my timid nature struggles to realize…I want everything to be perfect, to have good reason to believe in success, before I try something. How often do I stifle God’s promptings because I can’t see how it would turn out well?

Nicely said!

Pointing to the courage that underlies greatness is significant and a challenge to us all. But it sure requires much MORE to be considered great than simply being “convinced of their greatness, their genius, their skill, and that fact leads them in everything they do.” Moreover, there have been many greats whose humility and (appropriate) self-doubt was an important mainstay of their character and capacities. Abraham Lincoln and Winston Churchill come to mind.

With that in mind, I was disappointed by your choices of modern-day examples, particularly Clinton and Dawkins. Dawkins for many of us appears to have become a philosophical fundamentalist, unable to see beyond his own quarter — see this rather damning quote from (former) atheistic scientist Anthony Flew.

“With every passing year, the more that was discovered about the richness and inherent intelligence of life, the less it seemed likely that a chemical soup could magically generate the genetic code. The difference between life and non-life, it became apparent to me, was ontological and not chemical. The best confirmation of this radical gulf is Richard Dawkins’ comical effort to argue in The God Delusion that the origin of life can be attributed to a `lucky chance.’ If that’s the best argument you have, then the game is over… I would add that Dawkins is selective to the point of dishonesty when he cites the views of scientists on the philosophical implications of the scientific data. Two noted philosophers, one an agnostic (Anthony Kenny) and the other an atheist (Nagel), recently pointed out that Dawkins has failed to address three major issues that ground the rational case for God. As it happens, these are the very same issues that had driven me to accept the existence of a God: the laws of nature, life with its teleological organization and the existence of the Universe.’ “

Hmm..isn’t it interesting how God just gives you exactly what you need right when you need it. I’m preaching on the parable of the talents this coming Sunday and was randomly searching the web for stories about risk-taking, hoping to find a story about someone who took a risk and ended up using their gifts in a way that impacted other people or the world in a major way. I stumbled across your article and was taken aback to discover that you were linking Michelangelo’s story to the parable of the talents. Wild!