I was pregnant, I wanted to keep the baby, but I had to realistically acknowledge that I was far too immature to raise a child. How could I penalize a baby that way? Adoption. … My maternal instincts are frighteningly strong, and it would have been like tearing my heart out to put my baby into a stranger’s arms. … I know my decision to have an abortion was the right one for me. —Tonia Vogel, Scarred for life by painful, illegal abortion, Arizona Daily Star Op-Ed, March 26, 2006

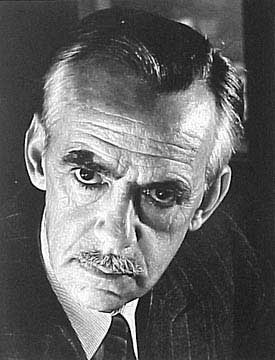

His father was a fine stage actor—famous, successful, yet bitterly disappointed that talent and hard work had not been enough to achieve greatness. His mother was a saint whose beautiful spirit had been crushed over the loss of a child to measles. She became addicted to morphine and withdrew into a private world of drug-dimmed grief and regret.

His father was a fine stage actor—famous, successful, yet bitterly disappointed that talent and hard work had not been enough to achieve greatness. His mother was a saint whose beautiful spirit had been crushed over the loss of a child to measles. She became addicted to morphine and withdrew into a private world of drug-dimmed grief and regret.

Into this house of sorrows came an unwanted child: Eugene Gladstone O’Neill, perhaps America’s greatest playwright.

Family is the fiery crucible where a man and a woman embrace with all of the hot passion humans are capable of, both creative and destructive, passions from which new life is conceived and nurtured, so vulnerable, so fragile in body and spirit, absorbing every lesson in the human drama as they are acted out day by day—lessons in love, sacrifice, compassion, self-denial, faith, but also lessons in hate, hurt, emptiness, failure, doubt—and from this slag-encrusted crucible, God’s children are poured into molds where they cool and crystallize into fully-formed human beings.

The process is not pretty; the product is never perfect.

In O’Neil, this crucible of trouble and neglect produced a young man who was deeply scarred. He was married three times, the first two resulting in three children. But fatherhood sent him into a panic and he bolted and never looked back. For years he wandered aimlessly in South America, drinking heavily and wasting away. When he was 23—penniless, miserable, having failed to find any reason to live—he attempted suicide, and failed at that, too.

At the end of his rope and barely alive, Eugene O’Neill turned to writing. Over the long span of his career as a playwright, this unsmiling, broken down human being earned 4 Pulitzer prizes, the last one awarded posthumously for Long Day’s Journey Into Night. In 1936 he won the Nobel prize for literature.

I remember reading The Iceman Cometh in high school. It was stunning. O’Neill’s writing is beautiful for its sparse clarity, and his characters are unforgettable, exquisitely drawn from the pain of human experience, not often admirable but terribly real in their self-inflicted agonies.

It is tempting to think that O’Neill’s life was utterly dark; it was not. In his youth, he believed in God. As his mother’s health deteriorated, he rejected faith, but never completely. He found peace, even joy, in solitude by the ocean, immersed in the beauty of the created world. He seemed to have a sense that he was part of something bigger, something more significant than his small and tortured life, and that gave him pleasure.

But his greatest love in life was writing. He wrote and researched tirelessly, pouring out stories about the human drama that awed and moved his audiences.

So, the obvious question: Would it have been better for Eugene O’Neill had he never been born? Would it have been better for his mother if she had chosen to abort him?

When he was 23, O’Neill himself answered “yes.” But it is interesting that after that suicide attempt, despite suffering all sorts of mental anguish and dark moods, O’Neill found fulfillment and joy in his life as a writer.

We tend to hold romantic notions about family life, especially when debating socio-political issues. In the real world, creating a good family is the most difficult work two people can do. And in this age of casual couplings, instant divorce and absent parents, the challenges are greater than ever.

Our lack of commitment to family is creating damaged children, scarred children, children who are likely to fail at marriage and child-raising themselves because we have been such poor role models.

But the very worst of our sins against family are being committed by the millions of young Tonia Vogels playing God with their unborn babies. They look at their own lives, they peer into some cloudy crystal ball, and they somehow convince themselves that this new life growing inside of them would be better off never being born.

Among the millions of babies aborted every year, we have undoubtedly deprived the world of a great many bright stars like Eugene O’Neill.

We are not wise enough to play God. We are too broken to be entrusted with children. If ever we needed God’s merciful grace, it is in our families.

Photo credit: Horace Bristol

Yes, this is the heart of the matter — life is not pretty, but we must live it anyway. Trust God to do the beautifying. Every life is indeed precious.

I find Vogel’s statement astonishing: her maternal instincts are so “frighteningly strong” that she couldn’t give away her live baby to someone who could raise it…she had to kill it instead???

Bonnie,

I believe the women have to convince themselves that it’s a pregnancy, just tissue, not really a baby yet, and then they can go through with an abortion and keep themselves from having to face that it’s a baby they’re giving up. The power of the human soul to lie to itself and then believe those lies is enormous. God help us all.