Phone booths have all but vanished from the American landscape, to the delight of the myriad faceless number crunchers who toil at Verizon, AT&T, Sprint, and T-Mobile. It’s bad enough that the extinction of the public telephone has created so much hardship for cellphoneless citizens like myself, but far worse is the chilling effect it has had on the crime-fighting work of Superman. I am not the first to note that as phone booths and pay telephones have been uprooted from street corners, sightings of the Man of Steel have become few and far between.

Phone booths have all but vanished from the American landscape, to the delight of the myriad faceless number crunchers who toil at Verizon, AT&T, Sprint, and T-Mobile. It’s bad enough that the extinction of the public telephone has created so much hardship for cellphoneless citizens like myself, but far worse is the chilling effect it has had on the crime-fighting work of Superman. I am not the first to note that as phone booths and pay telephones have been uprooted from street corners, sightings of the Man of Steel have become few and far between.

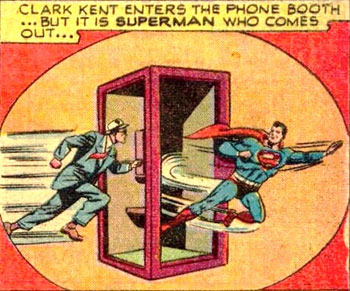

Keep this to yourself, but I have it on good authority that Superman is actually mild-mannered Clark Kent, a reporter for the Daily Planet. When a citizen is attacked by a mugger or a child walks in front of a bus, the ace reporter excuses himself from whatever he is engaged in, dashes into the nearest phone booth and removes his suit to reveal his Superman costume. He then flies to the rescue, leaving his hat and clothing behind for some lucky bum.

The Man of Steel’s Men’s Warehouse bill must be enormous.

Hollywood got a laugh out of Superman’s modern plight in the 1978 movie version of Superman. The Man of Steel, played by the late Christopher Reeve, dashes off to rescue Lois Lane. Pausing beside a modern, open pay telephone, he does a double-take as he realizes that it simply won’t do as a changing room.

Hollywood got a laugh out of Superman’s modern plight in the 1978 movie version of Superman. The Man of Steel, played by the late Christopher Reeve, dashes off to rescue Lois Lane. Pausing beside a modern, open pay telephone, he does a double-take as he realizes that it simply won’t do as a changing room.

Here’s the thing: Everyone knows that Superman does his quick-change thing in a phone booth, right? Except that this turns out to be something close to an urban legend. Researchers at the Superman Homepage have scoured the primary sources, only to discover that in most of Superman’s adventures over the decades, he has usually changed clothes in alleys or closets or right out on the street. In only a few instances has he ever used a phone booth. The very first time seems to have been in a 1941 animated short film called “The Mechanical Monsters.”

So how did phone booths become synonymous with Superman? Perhaps enough movie-goers saw that 1941 cartoon to create a lasting cultural connection between Superman and phone booths, a connection that has been stuck in our collective imaginations ever since.

Which raises the question: Do we hold other beliefs which, if examined, might turn out to be rooted more in myth than fact? How do we know what we know, and how do we know that what we know is true?

Not that many years ago, white southerners commonly believed that blacks were racially inferior. In the late 1930s, many Germans believed that the decades of economic hardship their country had endured following the Treaty of Versailles had been engineered by powerful Jewish political and economic interests. These are worst sorts of groupthink, pernicious lies that take root in our collective consciousness and quickly establish themselves as unquestionable fact, only to be passed along from one generation to the next.

We all hold to a set of beliefs about the world we live in, including beliefs about ourselves, about life and the way things work, or ought to work. Most of these beliefs come to us from some combination of our personal experiences and the things we have been taught by our family, our teachers, or gleaned from influential books or things we’ve read online. We hold to these things as if they were facts, but sometimes, on closer examination, they turn out to be flat wrong.

In this era of modernism, as we have embraced a science-based, reason-centered approach to knowledge, we have uncritically adopted a bias towards ideas that can be proven via some scientific method, and against those that cannot. Facts, or things that appear to be facts, are given more credence than beliefs, especially religious beliefs, the assumption being that this is exactly as it should be.

And yet, there is a good deal of unproven hypothesis — faith — in modern science. The recent possibility that the Higgs Boson has been discovered at the LHC in Switzerland fills in an important gap in the Standard Model of particle physics. Yet, the Standard Model itself is a radical simplification that fails to explain some rather important things, such as gravity, or the nature of “dark matter” and its role in the expansion of the universe. The Standard Model is factual — provable — as far as it goes, but doesn’t speak to a number of things that are accepted by faith, because they can’t yet be proven.

So we are encouraged to reject faith, and the sort of revealed knowledge we find in the Bible, while at the same time we are encouraged to embrace as fact a great deal of science that is little more than the outcome of an opinion poll — as in “97% of climate scientists agree that climate-warming trends over the past century are very likely due to human activity,” from NASA.gov, even as climate models fail to predict actual climate trends, global temperatures have plateaued, and storm patterns remain stubbornly in line with historical norms.

I don’t mean to pick on the global warming faithful, because in fact there are a great many religious beliefs masquerading as rationalism in scientific dogma. That is to be expected; our world is staggeringly complex and full of mystery. We just need to be more honest about the gaping holes in our knowledge.

This is how one writer has described the fact vs. belief bias of modernism:

The generally held assumption that doubt is more intellectually respectable than assent to a creed is one that must itself be criticized. … It assumes that ultimate reality is unknowable. It insists that truth claims about God and the nature and destiny of humankind must be in the form “This is true for me,” not in the form “This is true.” Confident statements of belief about such things are regarded as arrogant. It is assumed that there are statements of what is called “fact” which have been — as we say — scientifically proved; to assert these is not arrogance. But statements about human nature and destiny cannot be proved. To assert them as fact is inadmissible. They can never be more than “how it seems to me,” or “My personal experience,” or — even more typically — “How I feel.” — The Gospel in a Pluralist Society, Lesslie Newbigin

It is as dangerous to blindly reject faith because it sits on a foundation of untestable revelation as it is to blindly accept a scientific perspective built on a house of cards constructed from hypothesis, consensus, and politically driven fads. Faith is not the abandonment of reason. Quite the contrary, it is the pursuit of truth right up to the edge where reason can carry us no further, and then gazing past that point with the help of a different set of eyes, the eyes of our Creator.

Somewhere along the way, as phone booths disappeared, it occurred to Superman that he could simply change his clothes at super-speed right in the middle of a busy street and no one would see anything more than a blur. He might have opted to give up his secret identity; instead, he stayed true to himself and merely adapted to a changing world.

Modernism would prefer that we be done with faith, with religion, with these allegedly superstitious beliefs in an immaterial God. And in truth, we might be mistaken about all of that. Even if we are, it is not irrational to acknowledge mystery, to be in awe of the marvels of our world, and in those things to see evidence of the hand of a creative God.

The world changes. Phone booths will likely never make a comeback. Doubt tries to convince us to be done with God, but God is far from done with us. He waits for us to make an inquiry, as the phone booths topple, about whether there is one unchangeable and sure Presence behind all that we see, and all that we don’t yet know.

Well said. There are too many fields of investigation that have been removed from debate and replaced with ideologically obligatory positions, i.e., positions which can cost you the right to a hearing, your job, or maybe your life, if you question them. These are areas of inquiry like origins, social justice, climate change, religion, morals, the nature of reality, etc., which at one time could be freely studied and written about but which in our time are more safely avoided, unless you are prepared to subscribe to points of view that have been established by those at higher levels of power and influence. The search for knowledge and wisdom is being replaced by a steady advance of dogmatism. The first response to these realities is surely awareness. Beyond that, we could all use a good dose of humility, and then maybe gratitude for all of the good we have received.

I love this article how us Christians must meet the challenges of a changing society without compromising our beliefs and our faith in God. As Paul said (I’m paraphrasing) we are not of this world. Thanks so much.