In both 2000 and 2004, the most reliable indicator of a voter’s support for one presidential candidate or the other was that voter’s commitment, or lack thereof, to religious faith. Most pundits were predicting a similar result this year, which explains the massive effort by the Democratic party to convince us that its candidates know something about faith, too.

In both 2000 and 2004, the most reliable indicator of a voter’s support for one presidential candidate or the other was that voter’s commitment, or lack thereof, to religious faith. Most pundits were predicting a similar result this year, which explains the massive effort by the Democratic party to convince us that its candidates know something about faith, too.

But while attitudes about faith may still play a role on November 4, it seems clear that there is an issue of far greater relevance than religion to the outcome of this election, and that is race.

Hardly surprising, given the battered racial baggage that black and white America still carries some 156 years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

I believe America wants to be true to the vision of E Pluribus Unum. But with the deep wounds of such injustices as the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision, Jim Crow laws, and the present day gulf between blacks and whites in dozens of indicators of social progress, it is little wonder that race still divides us.

Barack Obama’s candidacy is testing just how much America’s racial attitudes have changed. Pundits have been hyper-vigilant to any perceived racial insult, jumping on John McCain, for example, when he recently referred to Sen. Obama as “that one” in a debate. Pollsters are worried about the “Bradley/Wilder effect,” a theory that whites may be less than honest when asked about their reluctance to vote for a black candidate.

Less talked about is what I call the “Ward Churchill effect,” in which some whites will reflexively embrace Sen. Obama as an act of faux atonement for the myriad sins committed against blacks in our American past. In an equally symbolic gesture, many blacks will undoubtedly vote for Barack Obama for no other reason than their (understandable) pride in his achievement — in neither case will his actual political views matter.

Like it or not, the politics of race is thoroughly infused in this election, as it is in our culture at large. Given our history, it could hardly be otherwise.

In a pluralistic society built on the principle that “all men are created equal,” using race as an excuse to deny justice or equality of opportunity is immoral. But racial differences are real, and it is not immoral to acknowledge them. It is foolhardy not to.

We are not colorblind. It is an intrinsic part of our human nature to classify and categorize, and the most basic of all human divisions is “myself” and “other.” Classification can be abused, but it is not intrinsically wrong. We see differences. We experience differences. Our differences create social challenges, for sure, but they also stretch us and make us better.

Just as Darwin observed that the smallest differences can create sweeping benefits for a species, a truly enlightened political system will not seek to Balkanize society along racial lines. Rather, it will encourage blacks and whites (and Asians and Hispanics and…) to apply their individual talents together to make society better for all.

Unfortunately, some see greater political gain in encouraging racial grievances than in promoting unity.

Mona Charen had an interesting observation about the distinction between equality of condition and equal opportunity, a distinction that has been blurred in our conversations about racial justice.

[T]here is no such thing as a totally equal society. (Nor is it desirable.) Even in places like Sweden, some are born into loving, wealthy two-parent families and others are born to alcoholic single mothers. Some have good looks and talent, others don’t. No society south of Heaven can ever be completely equal. But the essential justice of a society is measured, I believe, not by whether you have equality of condition but by whether you have equal opportunity. — Mona Charen, National Review, 21 Oct 2008

The real sin of racial politics is that it invites us to make sweeping and erroneous generalizations, blinding us to that God-breathed individuality that trumps our racial identity. And we know from history how much easier it is to demonize a group than an individual.

I have several German friends who are very uncomfortable about America’s unabashed nationalistic patriotism. Germans love their country in much the same way Americans do, but their history includes the awful tragedy of National Socialism, a prideful nationalistic movement that nearly destroyed all of Europe. The stain of Nazism has made ordinary Germans ultra-sensitive to the potential dangers of patriotism. From a racial and superficial perspective, Germanic people are very similar to white Americans, but their political beliefs have been shaped by a very different history, giving them a radically different take on their personal and national identity.

Racial stereotyping makes it easy to assume that we already know all that is worth knowing about someone and excuses us from making an effort to discover their individuality.

Perhaps the most shocking revelation the first century Jewish Christians had to come to grips with was that God was bringing Jews and Gentiles together as equals at the foot of the cross. The implication for the Jews, who had lived under a strict ethic of racial purity and segregation since the time of Moses, was that they had to set aside the apartheid they had been taught as children and learn to embrace people who had always been their religious and cultural enemies.

The Apostle Peter was the first to confront this dramatic change when he was instructed by the Holy Spirit to visit Cornelius, a Roman army officer. Cornelius was a devout worshipper of the God of Israel, which was not unheard of in itself. Gentiles could worship Israel’s God in a separate-but-equal fashion, so long as they kept their distance from the Jews.

When Peter entered Cornelius’ home, he was in violation of the Jewish laws commanding racial separation. Nevertheless, he obeyed his orders and began preaching to Cornelius, his family and servants about the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Then, God did something shocking:

No sooner were these words out of Peter’s mouth than the Holy Spirit came on the listeners. The [Christian] Jews who had come with Peter couldn’t believe it, couldn’t believe that the gift of the Holy Spirit was poured out on “outsider” Gentiles, but there it was — they heard them speaking in tongues, heard them praising God. Then Peter said, “Do I hear any objections to baptizing these friends with water? They’ve received the Holy Spirit exactly as we did.” Hearing no objections, he ordered that they be baptized in the name of Jesus Christ. Then they asked Peter to stay on for a few days. — Acts 10:44-48, The Message

Christian Jews and Gentiles did not find it easy to unlearn the habits that had separated them for centuries. The Christian church has not always gotten the question of race right. To its credit, however, it was the Christian church that led the anti-slavery fight in the Civil War, as well as the more modern movement that overturned American apartheid in the twentieth century.

Now, the American Christian church is faced with yet another historic opportunity to transform the divisive racial politics that still grips our nation. Evangelicals are tending to support John McCain in this election. If he wins, there will be bitter accusations that the white establishment has wielded its power to deny Sen. Obama his rightful place in history. If Barack Obama wins, white evangelicals may be tempted to criticize him in ways that will seem racially motivated. It is possible that this election will deepen our racial divisions, no matter what the outcome.

That would be a terrible tragedy. Black and white Christians may be more divided by this election than at any time since the Civil War. We can hope and pray that both black and white Christians will come to realize that the God we worship does not look at us through the lens of race or sex or national origin. The God of the New Testament sees us as children whom he has rescued and adopted. Black and white alike, we have all been bought by the costly and precious blood of Jesus Christ.

The politics of race gains strength by pitting us against each other. The message of Jesus Christ is that sooner or later, we will have to learn to live under the same roof.

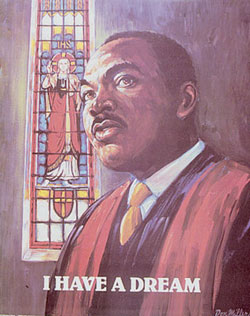

Graphic credit: Don Miller

Comment Policy: All comments are subject to moderation. Your words are your own, but AnotherThink is mine, so I reserve the right to censor language that is uncouth or derogatory. No anonymous comments will be published, but if you include your real name and email address (kept private), you can say pretty much whatever is on your mind. I look forward to hearing from you.