Once a computer achieves a human level of intelligence, it will necessarily soar past it. … Will these future machines be capable of having spiritual experiences? They certainly will claim to. They will claim to be people, and to have the full range of emotional and spiritual experiences that people claim to have. And these will not be idle claims; they will evidence the sort of rich, complex, and subtle behavior one associates with these feelings. —Ray Kurzweil, computer scientist and author of the book The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence

Ripley: You never said anything about an android being on board…

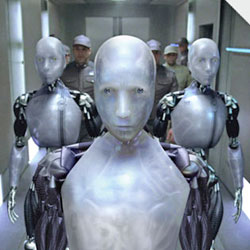

Bishop: I prefer the term “Artificial Person” myself. —Aliens

We came from the stars, and to the stars we shall return. This poetic view of life is held by materialists, for whom nothing exists but that which we can touch, test and verify.

We came from the stars, and to the stars we shall return. This poetic view of life is held by materialists, for whom nothing exists but that which we can touch, test and verify.

An instant prior to the Big Bang, all of the material universe was squashed into a super-heated singularity. Having reached some critical limit, it exploded with unimaginable violence. Over millions of years, the universe expanded, cooled and coalesced. Stars formed, and in the bellies of the stars nuclear fusion forged the elements of the periodic table. There were more explosions and these raw materials were strewn far and wide. In our own solar system, this primordial hydrogen, oxygen and carbon became earth stuff, plant stuff and even the stuff that gives shape and life to our own bodies.

Modern materialists and the Stoic philosophers of ancient Greece share a common belief: there is nothing more to life, history and the universe than matter, energy and eons of time.

Ray Kurzweil is a brilliant computer scientist and a thorough-going materialist, though he prefers the term “patternist.” Kurzweil works in the rarefied field of artificial intelligence where he pursues the holy grail of engineering: a machine that can think like we do. Kurzweil is absolutely certain such a machine is possible—in his view, we ourselves are machines: thinking machines, spiritual machines. To create an “artificial person,” scientists will find a way to reverse-engineer the human brain, allowing them to duplicate in doped silicon what evolution has rendered in protein.

When Kurzweil speaks about “spiritual” qualities, he means those qualities that separate us from the lesser animals: emotion, consciousness, imagination and the like. To Kurzweil, these spiritual qualities make human beings the crowning achievement of the evolutionary process.

If we are spiritual machines, and human life is nothing more than the software programming of our brains acting on the stored data of our experience, this Brave New World of human reinstantiation will give us a genuine shot at immortality. We will upload our minds into an artificial person and live on for centuries, long after our physical bodies have turned to dust. Instead of heart transplants, we’ll have CPU and RAM upgrades. Human life will have no end point—everyone will be eligible for senior discounts! Public service announcements will remind us to back up our minds daily and always keep a supply of fresh batteries on hand.

But suppose the underlying supposition is false? What if there is something more than just this material universe? What if we’re not machines at all? What if there really is a God who created us in his own image, for his own pleasure? Should we expect such a Creator to show any interest at all in a bunch of polyethylene, human knock-offs?

Then God said, “Let us make people in our image, to be like ourselves.” … And the Lord God formed a man’s body from the dust of the ground and breathed into it the breath of life. And the man became a living person. —Genesis 1:26, 2:7, NLT

You made all the delicate, inner parts of my body and knit me together in my mother’s womb. Thank you for making me so wonderfully complex! Your workmanship is marvelous—and how well I know it. —Psalm 139:13-14, NLT

When I look at the night sky and see the work of your fingers—the moon and the stars you have set in place—what are mortals that you should think of us, mere humans that you should care for us? For you made us only a little lower than God, and you crowned us with glory and honor. —Psalm 8:3-5, NLT

The Judeo-Christian view is that we are imageo Deo, made in the image of the One, True, Eternal God. We are not spiritual machines; in fact, we have no innate ability to reach out and touch the spiritual realm. Rather, God reaches out and touches us. Our participation in the spiritual is all at the initiative of the sovereign King of the spiritual. We are significant because God thinks of us. We have value because God formed us. We are spiritual because God desires a relationship with us.

Materialists have gotten off at the wrong station. If Kurzweil and his colleagues ever succeed, their creations will turn out to be “spiritless machines,” magnificent doppelgängers utterly convinced of their humanity but absolutely devoid of heart and soul. Imagine great armies of artificial persons trapped forever in a meaningless existence, their hardware constantly improved but their “lives” serving no remembered purpose. Fearing death, these sad beings would have literally traded their souls for the gold ring of immortality, only to discover that what they’d snatched was made of brass.

If a shepherd has one hundred sheep, and one wanders away and is lost, what will he do? Won’t he leave the ninety-nine others and go out into the hills to search for the lost one? And if he finds it, he will surely rejoice over it more than over the ninety-nine that didn’t wander away! In the same way, it is not my heavenly Father’s will that even one of these little ones should perish. —Matthew 18:12-14, NLT (Jesus speaking)

The essential difference between human cyborgs and human beings will always be this: machines have no intrinsic worth—they are stamped out on an assembly line and destined for the scrap heap; humans are individually conceived, crafted and cherished by the God who calls us his children, the God who will not permit even one of his “little ones” to be lost.

Are we spiritual machines? Or are we children of the living God? There’s a lot riding on your answer.

Even if materialism is true, it doesn’t follow that making a computer program modeled after your thought processes means you can be immortal. After all, you can do that and still continue where you are in your own brain and body. No one would think the computer program is you then. Why would it be you even if you happen to die right as the program goes online?

It’s an interesting puzzle. In what respect would a computer that exactly modeled your mind, had all of your knowledge and memories, exhibited all of your idiosyncracies, and thought of itself as “you” not really be you? Kurzweil and others would say that the essential us is what is in our mind, and if your body dies and a perfect clone of your mind lives on, in fact, it is you that continues to live.

I think the materialists error is that our identity is not held within us, but is given to us by an external agent, God our Creator.

My problem is that I’m still here. Are you suggesting that I’d be in two places at once? How can making a copy of me mean it’s me? Even if you took every detail of my body and made a duplicate, it wouldn’t be me. It would be a duplicate. The same is true of my mind. The fact that my body and mind can continue on even if you do this is what shows this. So I just don’t see why it would be me surviving immortally. It would be a copy of me. It may even be the kind of thing were everyone would think it’s me, but I maintain that they’d be wrong. This is my biggest criticism of the view most of the characters took in The Sixth Day. At the end we saw a clear example of why it can’t be right, both the dying original and the copy existing at the same time, each thinking he had every right to say he was the original.

You’re right. You’d still be here. You can know subjectively that you are the real Jeremy. Others can only know you objectively, and they may have trouble knowing which is the real you. And the copy? If it is a perfect brain copy, it will forcefully, subjectively believe and insist that it is you.

Doesn’t matter. You know the truth. You’re you.

But what does that mean? This is where Kurzweil develops his thinking in the area of patterns, and why he calls himself a patternist (a concept I didn’t take the time to explain.)

Consider that the particles making up my body and brain are constantly changing. We are not at all permanent collections of particles. The cells in our bodies turn over at different rates, but the particles (e.g., atoms and molecules) that comprise our cells are exchanged at a very rapid rate. I am just not the same collection of particles that I was even a month ago. It is the patterns of matter and energy that are semipermanent (that is, changing only gradually), but our actual material content is changing constantly.

He draws the analogy of a stream of water that is flowing past a large boulder. It has a pattern of flow, an appearance of turmoil, eddies, etc. that seem not to change. But what we observe is a pattern—the actual matter making up that pattern changes every millisecond.

So it could be said that “I” am more of a blueprint than a constant material being. In fact, the heart of the aging process is that the cell-by-cell, atom-by-atom replacement that is going on constantly in my life gradually creates enough errors that things start to go awry.

Kurzweil suggests a thought experiment. Suppose you developed a problem with a small group of neurons in your brain, and it was possible to replace them with a small chip that perfectly replicated the functions of those neurons. You have the surgery. You recover. You feel and think and seem the same as before. But now, part of your biological mechanism has been replaced with a functionally identical part (patterned after the biological). Suppose you repeat the procedure, and gradually more and more of your brain is replaced with electronic equivalents. At each stage, both you and your friends are convinced that you are still the same old you.

…the gradual replacement scenario is not altogether different from what happens normally to our biological selves… So am I constantly being replaced with someone else who just happens to be very similar to my old self?

But consider this. The gradual replacement of my brain with a nonbiological equivalent is essentially identical to the following sequence: (i)scan Ray and reinstantiate Ray’s mind file into new (nonbiological) Ray, and then (ii) terminate old Ray.

Peter Singer says some very similar things when he lectures about his utilitarian philosophy, which finds that in a materialist world, such policies as elective infanticide, suicide and euthanasia can be morally justified because there is no intrinsic value to a life that is not wanted, or enjoyed, or one that does not meet certain objective standards of quality.

If we are merely patterns of cells and particles which happen to be arranged to hold certain subjective ideas (I am significant, I am unique, I am special, I deserve to live), but which from an objective viewpoint have no more value than any other collection of cells, which view of my own humanity rules: the collective view of society about me, or my view about me?

What does it mean to be me if I am more of a pattern than a permanent organism?